In August 2023, teachers on TikTok claimed children couldn’t read. People then focused on a stat that said 65% of fourth graders are not reading at grade level.

The National Assessment for Education Progress (NAEP) report said:

In 2019, some 35 percent of 4th-grade students and 34 percent of 8th-grade students performed at or above NAEP Proficient

This triggered an online debate about so-called Generation Alpha, Gen Alpha, or iPad kids.

Those born in the early 2010s.

A debate about whether Gen Alpha are doomed and who, or what is to blame.

As teachers, parents, and young adults joined the conversation, YouTube videos like “The Tragedy Of Gen Alpha” gained millions of views.

But I had questions these videos weren’t answering:

- Are the numbers that bad?

- What are teachers doing wrong?

- Is the educational science being followed?

- Is Generation Alpha really unteachable?

Those are the questions I will look explore in this article.

The numbers don't support the claims

If you are like me, you have probably heard adults complaining about children before.

I can’t find who originally said this, but this is a quote I have seen pop up a lot, which predates all of us. I think…

What is happening to our young people? They disrespect their elders, they disobey their parents. They ignore the law. They riot in the streets inflamed with wild notions. Their morals are decaying. What is to become of them?

But teachers are saying this time, it is worse.

Having just read the recent PISA report, I know reading performance has dropped, but 65% not being proficient in reading, seems a little extreme.

So let’s look at the numbers.

American reading proficiency

Most of the teachers talking on social are from America. So I looked into American stats.

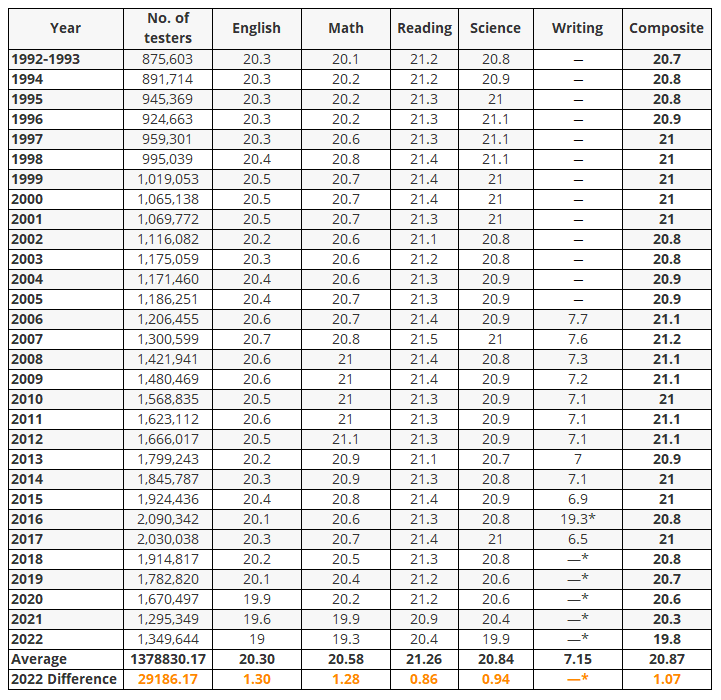

The average composite American College Testing (ACT) score, was used in conversation however, the score is combined.

Composite ACT scores combine Math, Science, English and Reading.

English focuses on writing, knowledge of language, and conventions of standard English, whereas Reading focuses on identifying key ideas and using that knowledge.

So the recent drop, might not be due to reading, but any of the other subjects.

These are the numbers I found.

You may notice a drop in testers since 2016.

But if we look at the average score from 1992 to 2022, and the 2022 scores.

The difference in Reading is the lowest of all the subjects. Suggesting reading proficiency impacts the composite ACT score drop, the least.

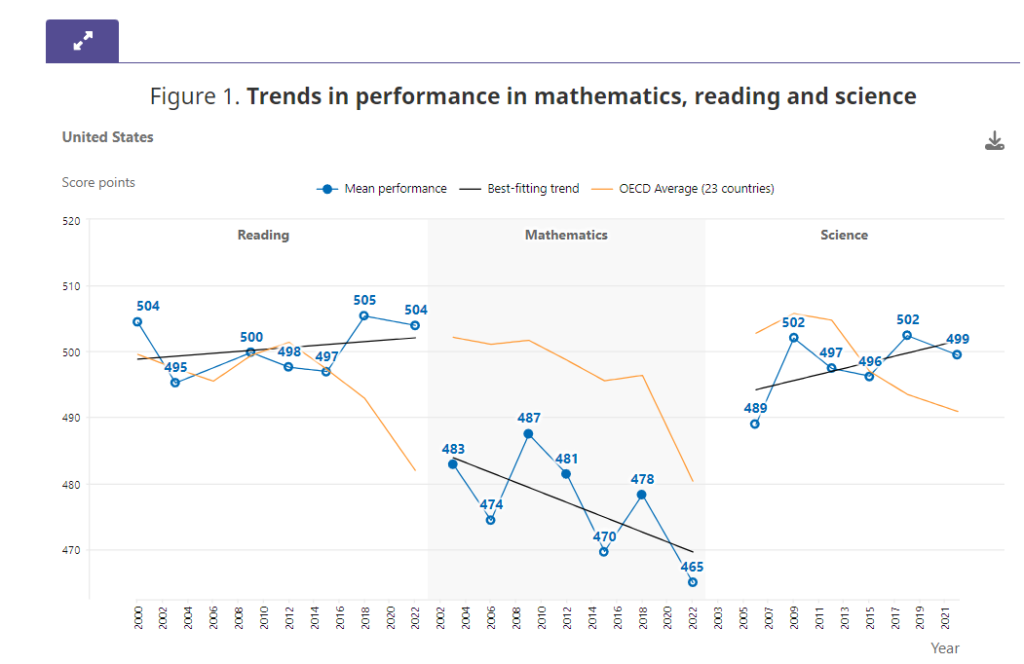

Then if we look at the American PISA scores. Reading seems to be getting better.

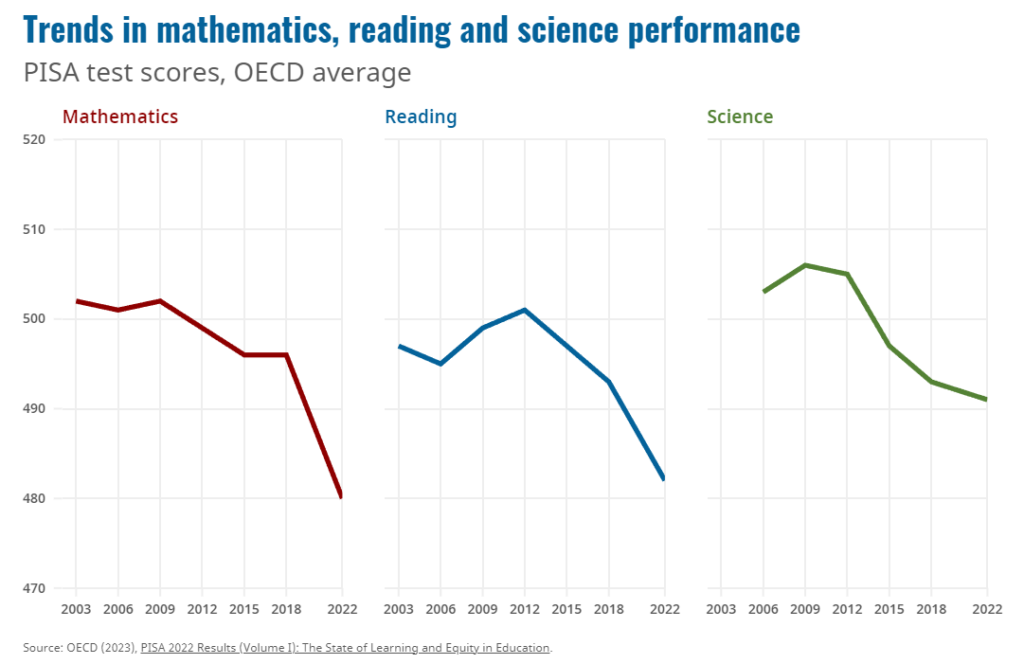

However, if we include other countries and economies, we see a drop in reading performance.

But that drop isn’t as sudden as some online commentaries are making it sound. And there has been a gradual decrease since 2009.

All that said, PISA tests 15 year olds and the ACT generally tests those above 13 years old, which is not generation alpha.

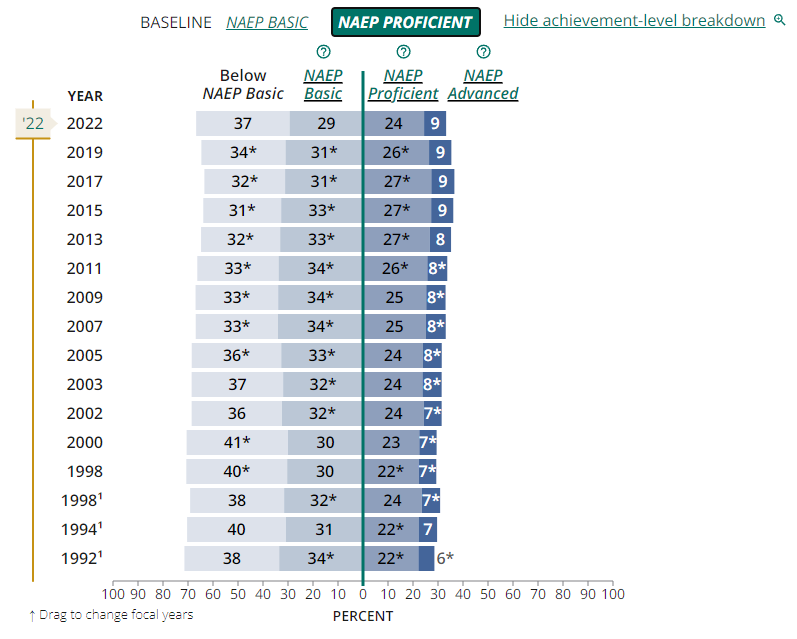

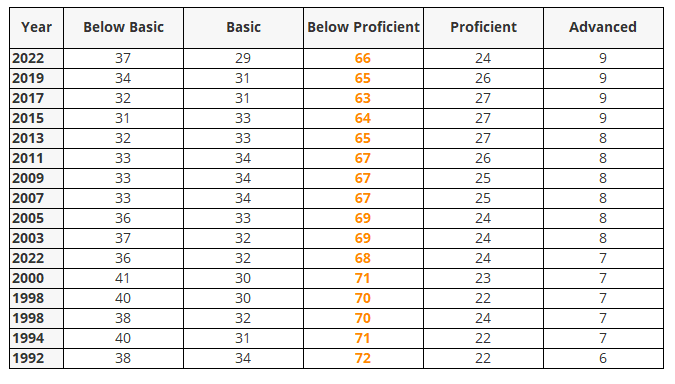

The 65% stat of grade 4 students not reading proficient is about Gen Alpha, but that was from 2019.

Recent 2022 stats show that 66% of Gen Alpha are not reading proficient.

However, there are a couple of things that stick out to me looking at the recent 2022 numbers.

First. 66% below proficient is better than 2011 and all the years before that.

Second. The 37% below basic hasn’t been that high since 2003.

And third. There are still 9% of students in advanced.

To me, this looks like a shift from basic to below basic, rather than proficient to below proficient.

Maybe that is what the teachers are seeing.

This begs the question. What does reading proficient mean?

PISA uses 8 levels of reading proficiency, whereas NAEP uses 4 different levels, with different names.

Teachers saying students are performing ‘below grade level‘ doesn’t help. Is that below proficient, or below basic?

The NAEP said:

Students performing at or above the NAEP Proficient level on NAEP assessments demonstrate solid academic performance and competency over challenging subject matter. It should be noted that the NAEP Proficient achievement level does not represent grade level proficiency as determined by other assessment standards (e.g., state or district assessments).

“Challenging subject matter” seems rather significant here.

Being above proficient is harder than being at grade level and “Equating NAEP proficient with grade level is bogus” as Tom Loveless said.

So although these numbers are important, and suggest a shift in where reading skills are, I don't think they support the extent of the claims made about generation alpha.

But there was a drop in basic reading, and performance at grade level is claimed to be decreasing, so are the teachers doing something wrong?

Teaching children to read isn't easy

When I was at school, I used to ask teachers, what is the point?

I won’t need this when I am older.

That's the first thing I thought about when considering Gen Alpha. They don't care about classroom tests.

Successful creators online talk about how they dropped out of school, or don’t think high school, or university is that important.

This could be influencing what the kids think about school.

Teachers can’t do much about the society at large, but they can control the classroom.

Teaching someone to read isn’t as simple as you might think. Or at least it wasn’t for me.

Before they can read they should be able to speak.

But everyone speaks differently. Accents, tone, and expression change how words sound.

Some children will know more words than others.

No child starts at the same point, developing at different rates.

Teaching with phonics

I had heard the term phonics before looking into this, but was never entirely sure what it meant.

Phonics is simply sounding out the letters and or combinations of letters. Turning letter symbols into sound words.

The letters and or combinations of letters are phonemes. The smallest unit of sound in a language.

Dog with /d/, /o/, and /g/.

Chain with /ch/, /ai/, and /n/.

Kids could go through a planned sequence of phonemes sounding them out, or sounds them out as they come to them while reading something, like a book.

Done with explicit instruction. Being told what letters should sound like.

And or, done with implicit instruction. The child figuring out the answer.

Both methods use feedback.

Words could be taught by sounding out the phonemes then putting them together, or learning the entire word. A sight word.

Sight words are words that students are expected to recognize instantly.

However, one of the TikTok teachers said sight words were used too much, which is why kids can’t read.

Words like the, once, come and walk.

But this is now about philosophy.

Conflicting teaching philosophies confuse the discussion

As teachers use their philosophies, the practice between teachers could be very different.

One teacher may call a word a phonic word, another teacher call it a sight word.

At first, you might not think it makes a difference. But it does!

Sight words are words that don’t follow phonic rules, so there is more reliance on memorization.

And for those that don’t read the educational science literature, memorization is useful but often criticized.

Common critiques of memorization include:

- Lower retention rates over time.

- Shallow understanding from learners.

- Less engaging for learners.

The TikTok teacher’s thinking was that using sight too much would lead to lower retention and less understanding of the words from the kids. Logical.

In that scenario, how can students learn words that aren’t sight words?

Either they aren’t taught, taught rarely, or teachers make non-sight words (phonic words), into sight words.

Teaching phonic words as sight words is where I think the conflict starts.

But the reading recovery program took sight words a step further.

According to episode 1 of a podcast, this program had children guessing the next word in a sentence.

Guessing words isn’t reading them.

Unsurprisingly, the long-term effects of the reading recovery program were significantly negative.

However many teachers may still use ideas and practices from the program.

The theory assumes learning to read is a natural process, and that with enough exposure to text, kids will figure out how words work.

I don’t entirely disagree with the theory, but I disagree with the reported practice.

Reading practice and performance

As each learner is different, I don't think there is a 'best way'. But some are more effective than others.

Rebecca Rolland Ed.D. wrote in a blog article:

as UCLA professor Maryanne Wolf discusses, that reading is a "natural" thing, and kids will just pick it up. Really, there's a specific "reading brain" that kids need to build, through targeted support and instruction, starting in the earliest years.

There are 3 key claims here:

- Reading is a natural thing.

- There is a reading brain.

- Targeted support and instruction is needed.

In episode 2 of the podcast they share another important claim:

Beginning readers don't have to sound out words.

Let’s address these claims one by one. Sort off.

As natural doesn’t have many guardrails on what it means or looks like, I will leave the philosophy out for this article. But I will expand on this claim later!

A reading brain sounds important.

But apart from knowing parts of our brain are active when reading, something I think that’s quite obvious, this doesn’t tell us much about how to teach people to read.

Developing skills through targeted support and instruction. That we can work with.

Targeted support and instruction are parts of practice.

So does the practice need to have readers sound out words?

This is where I think about individual experiences.

A learner, reader, has a different experience to an educator, teacher.

When teaching someone to read, the educator checks the experience of the reader.

If educators need to measure learner performance, there needs to be something to measure.

The sounds could be accurate, but the person may lack understanding of what the word means.

The sounds could be inaccurate, but the person may understand what the words mean.

For me, this is where the practice of a skill should represent the intended performance.

Reading aloud is a skill.

Reading to oneself is a skill.

Reading proficiency also includes the ability to:

- Understand texts and identify the main ideas.

- Interpret and evaluate texts considering author’s purpose, tone and perspective.

- Synthesizing information concluding multiple sources.

- Applying knowledge from texts like the following instruction.

Thus, teaching someone to read ends when they perform at the level desired or required.

With reading performance in school often being assessed by written tests, reading to oneself seems more representative than reading aloud.

However, educators often assess performance by reading aloud.

Thus the practice that would represent that skill the best would be reading aloud.

This could explain test disparities in those children who seem good at reading, reading aloud, but struggle on written tests, and those who seem bad at reading, reading aloud, but do well on written tests.

Practice not matching assessment.

A philosophy of natural reading

Natural can mean lots of different things.

In educational science, natural often refers to the body, typically the brain.

As said in episode 2 of the podcast:

Research shows human beings are born with brains that are wired to acquire spoken language. [...] we are not born with brains wired to read.

But that assumption, humans being wired to learn to speak but not read, to me is problematic.

Unless I am missing something, brain research shows brain activation, but nothing more.

We don’t know what the neurons are saying, meaning or doing when they activate. Only those parts are active when we behave in a certain way.

If we are wired to speak from birth, why does it take lots of time and teaching to learn?

Because people develop the skill of speaking through experiences. Empiricism.

The same can be said for becoming a skilled reader.

Saying 'we don't need to be taught to talk' is wrong.

There are loads of people that have specialist teachers to help them talk for various reasons.

If we want to learn a different language, we either get a teacher or teach ourselves.

Children brought up in the wild also need teachers to learn how to talk.

A more common example might be deaf people. They need to be taught to talk!

We don’t just have the information wired in our brains.

We learn through experience, empiricism, which is true for reading, speaking and all of the skills we develop.

The issue here is that the wired assumption is used to evidence some teaching philosophies.

As said in episode 2 of the podcast:

This process of connecting the pronunciation of a word with its spelling and its meaning is critical. Its how your brain stores the written form of a word in your memory.

But that conflicts with the wired assumption.

You can’t both have and not have the information at the same time!

These theories around memory come from cognitive psychology, and those psychologists support the concept of empiricism, learning from experience.

Saying 'human beings are born with brains that are wired to acquire' certain skills should be rejected.

Therefore ‘natural‘ should refer to something else.

Cognitive psychology relies heavily on theories in memory. The individual storing information for interpretation and or calculation.

But there are lots of different ways to use those theories, in practice.

And then Ecological Psychology takes a fundamentally different approach.

It looks at the organism-environment relationship rather than the individual.

The discussions about this have gone on for decades and will continue.

But philosophical differences don’t explain why teachers are saying Gen Alpha can’t read.

Kids don't care about learning to read

I mentioned earlier Gen Alpha might not care about classroom tests. Might not care about learning to read.

If reading is a skill, and the skill doesn't help them do what they want, why would they learn it?

We are all goal-directed.

Hungry? Go find food.

Bored? Do something else.

Behaviour is driven by a purpose or a goal.

Behaviour changes our experience, and we learn from our experiences so goals change our learning.

Pretty obvious, but that’s the logic.

Common advice I have seen about helping children to care about reading includes:

- Pick an interesting book format.

- Find interesting books.

- Pick challenging books.

- Take turns reading pages in a book.

But what if the person doesn’t want to read a book? or doesn’t like reading books?

Other advice I have seen:

- Talk through reading concerns.

- Get a vision test.

- Limit screen time on devices.

But none of those things give the child, or person, not interested in reading a book, a reason to read.

Give someone a reason to read

Most people discuss consequences. Not necessarily punishment but a result or effect. Yes, normally unwelcome.

Consequences strong enough certainly give a reason for a child to read.

The potential goals which impact behaviour:

- Avoid punishment.

- Avoid failure.

- Avoid unwelcome experiences.

However, if those goals can be achieved in a different behaviour, say:

- Messing around to be kicked out of class or sent home.

- Not doing the work.

- Copying others.

Then the consequences might be avoided by the children achieving a goal you don’t want them to have, due to the behaviours it results in.

Autocorrect has been suggested as a reason Gen Alpha can’t write well.

But that could be true for any person.

Assuming writers are reading the words, the words should be somewhat accurate.

If they’re not reading the words, it’s more drawing than writing.

I'm not saying spelling and grammar isn't important, it obviously is, but unless the person understands why they need to learn to spell, why would they?

Why learn an unused, or rarely needed, skill?

Reading academic papers is a skill people can learn.

Sounding out words. Understanding the jargon. Words.

Learning the meaning behind the words.

That’s still learning how to read.

But most people don’t learn how to read complex academic texts, because there is no reason to.

The same could be said for children, learning how to read basic texts.

Testing is an obvious reason, which I will cover later, but what other reason could there be?

Instructions to play a game.

Explanations on how to get something like an Easter egg hunt activity.

Or stories about characters they could be interested in.

There are lots of problems we could face where reading can help us.

This means reading involves a task environment.

I hated reading as a kid

When doing my reading homework I said the words from the book while my mum listened.

All I remember is paying attention to the page number.

10 pages and I can go play sport, or do literally anything else.

I didn’t know what I was reading, just that the sounds I was making must have been right. Until I was stopped to re-read a word.

Written English was my worst subject at school.

Spoken English was fine. Written. Nope.

Most of my school reports mentioned something like:

- He didn’t read the questions properly.

- He struggles to understand what the text says.

- He reads too fast and misses things.

But when I had a reason to learn to read, my interest in educational science, I became a competent reader.

The first book I read, and could tell you what the book is about, was an academic book I read at 19 years old.

Working together with learners is important

I have read the book, Becoming a Sports Coach, countless times now.

Not because I was told to read it, but because I chose to read it.

During my sports coaching undergraduate degree my head of course, James Wallis (editor of said book), mentioned he was releasing a book.

This was in a list of hundreds of options we could pick from.

It would also be freely available from the Uni library.

I spoke with James about his book, alongside all the other texts. Bringing up my distaste for reading.

And that conversation. Just the one. Felt like a shared decision to not only buy, but read the book.

Years of teachers saying I should read more. I should practice reading. Reading is good for me. Changed nothing. But this one conversation changed my behaviour.

I recognize the teacher-student ratio is different in classrooms.

But for students that ‘can’t read‘, how much of the decision behind their reading experiences is given to the student?

What is the level of co-agency in their learning experiences?

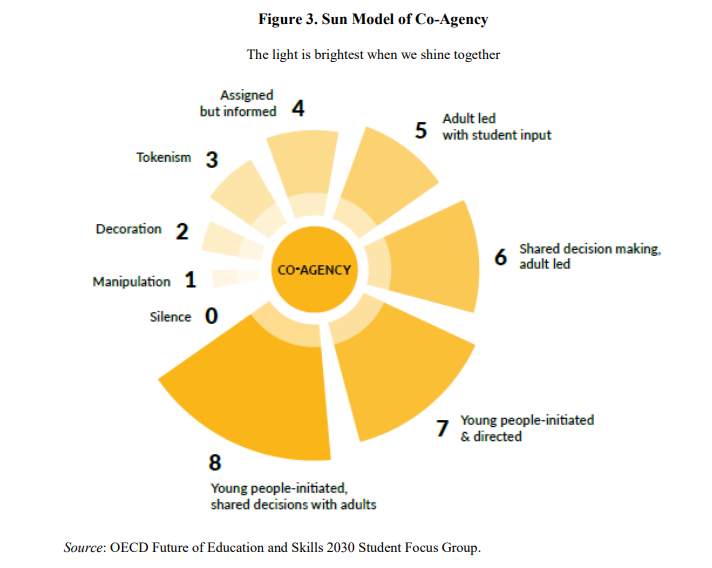

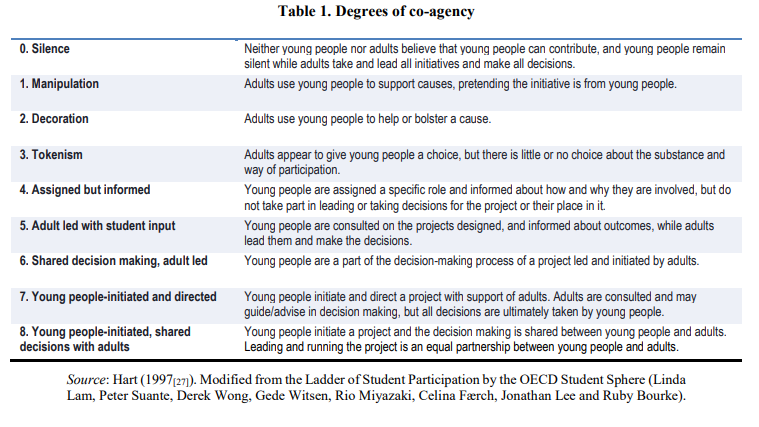

Essentially co-agency is the level at which people work together on decisions and directions for learning.

I find the Sun model from the OECD a helpful visual.

I suspect that most students in classrooms are expected to just do as they are told, with little to no influence.

Looking at this table from the OECD documentation, it may hover around the ‘tokenism‘ level.

In the documentation the OECD said:

The stronger the degree of co-agency, the better for the well-being of both students and adults.

To be clear, this isn’t just teachers and students. This includes parents, peers, and the surrounding community.

For me, this changes the question.

Instead of asking, what reason can I give a student? What reason can we come up with?

Reading tests are an obvious reason

Some of the previously mentioned consequences relate to tests.

Punishment in the form of no play, additional work, and in the past, physical punishment.

Now that could include, reduced phone time, social comparison, or a sense of disappointment from others.

Tests focus on a pass or fail.

The learner then looks to avoid failure.

Wherever that line is drawn.

Teachers, peers, and parents all potentially drawing different lines of failure, which shape ones own line.

There have been claims made some schools in America don’t test reading.

Oregon was a popular example of these skills not being needed, one example said:

an Oregon high school diploma will be no guarantee that the student who earned it can read, write or do math at a high school level.

But Senate Bill 744 says, Oregon emphasizes essential learning skills in the classes the students need to take to graduate, which include:

- Read and comprehend text.

- Write clearly and accurately.

- Apply mathematics in a variety of settings.

It sounds like reading is tested, just not in the same way as in other schools.

So not only are the lines of failure different. How skills are tested is different.

What does it mean to be literate?

If reading aloud, and reading to oneself are different skills. How do we test reading literacy?

Highly effective workers being tested on skills they don't use would show poor results.

The same could be said for learners being tested on skills they don’t practice.

However, reading and comprehension seem to be used interchangeably in these discussions.

But what does comprehension mean?

- Recognize the words?

- Put meanings to sentences?

- Have an understanding of the sentences. Is that a deep or shallow understanding?

Epistemology is the philosophical study of knowledge.

The words knowledge, understanding and comprehension can mean drastically different things.

A person’s level of expertise will change what it means to understand something.

One person may understand or comprehend something better than another because they have more expertise.

Yet, knowledge of doing something, is different, from knowledge about how to do something.

Reading comprehension could be about gaining meaning from words.

But if people are not familiar with the words, it might not mean anything, like me reading a foreign language.

I could read out the words but have no idea what it means, some words might sound right, some not.

Similar to complex academic jargon.

So reading and comprehension must be different things.

As mentioned above reading proficiency includes understanding, interpretation, synthesis and application.

For people with less expertise (those less proficient), typically younger, I would imagine the emphasis would be on identifying the main ideas and then applying knowledge.

Note, less expertise, because older children and adults also struggle with reading certain text.

But most people are literate.

They can read and write basic text.

However, a person’s level of expertise. How skilled they are. Is something that develops throughout learning experiences.

Again I want to emphasize, that if people don’t need to read or write complex text in their lives, why would they learn?

We are bad at testing reading expertise

Reading could be about decoding letter sequences into meaningful sequences of speech sounds. But I don't think it's that simple.

A basic set of universal skills, won’t solve all reading problems in everyday life.

If reading was just ocular scanning and symbolic comprehension, the environment wouldn’t matter. But it does!

Places, objects, people, and many other factors impact reading experiences.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t read step by step, even word by word sometimes.

Reading is therefore non-linear.

We go back and forth.

Re-read sections.

Skip sections.

Dictionaries are even designed to be pecked at. Dipping in and then out.

Reading could be the decoding of written words or successful comprehension of the meaning of the text.

However different criteria could be used to judge performance.

We could measure the speed of processing the text.

The rate of errors made.

Successful responses to questions of comprehension, or various other metrics.

Comprehension and fluency are popular criteria, but they don’t consider context. The task environment.

As a manifold task domain. Reading expertise could use different criteria in different contexts to judge performance leading to different results.

Social conventions, like English text going from left to right, from top to bottom, impact task environments alongside the problem.

We behave for a reason, often to solve a problem.

But when problem solving we could, and likely will, take different strategies:

- Reformatting the problem.

- Reconfiguring the problem.

- Abandon the problem, then return later.

Often simplifying the problem.

Reading to solve a problem in everyday life, is not as ordered as the practice used in educational systems, like schools.

An educator giving students a task, or a problem, will result in a variety of different task performances.

Each student reads differently, to help them solve the problem.

Testing reading expertise should therefore not be solely on the person, but on the functional system that solves the problem.

Juxtaposing task environment and task performance.

Expert readers in history, literature, sports and politics will read the text differently.

Expertise is domain and context-specific.

This also suggests skill expertise might not transfer, as alluded to earlier with reading aloud and reading to oneself.

A recent paper discussing reading expertise said:

the task environment does not include ‘reading’ as a basic level task, but only reading-as-embedded in-other-tasks.” [...] "a broader understanding of expertise in reading requires an appreciation of the cultural cognitive setting within which the activity of reading is being performed.

Readers with greater expertise, or skilled readers, would be able to deal with task environment challenges more flexibly than novice readers.

The reading test results used in schools therefore give a very narrow score on a person’s reading ability.

The usefulness of said scores is therefore up for debate…